- VClikeABC

- Posts

- What Is Venture Capital Really?

What Is Venture Capital Really?

A primer on Venture Capital.

If you’re here, it’s because you want to learn more about venture capital and how exactly it works. When I started in VC, I found it really difficult to find thorough and straightforward explanations for many concepts online, and the goal of vclikeabc is to remedy that.

To kick things off, we’re starting with an explainer on what exactly venture capital is, and what it isn’t, to set the foundation right.

So, what is venture capital?

Here’s a simple, straightforward definition:

Venture capital (VC) is money given to young, high-potential companies (startups) to help them grow quickly in exchange for a share of ownership in the business.

What venture capital is not: it is not a loan, it does not provide guaranteed returns, and it is not suitable for most businesses.

How does it work?

The venture capital fund invests capital and provides other forms of support, including advisory, strategic guidance, and access to its network, to help the startups it invests in scale. The fund eventually liquidates its positions in these high-growth companies and distributes the returns to its original investors. Although many startups fail, the high-risk, high-reward nature of VC investments means that a few successful investments can return the fund’s total invested capital, even if most yield losses.

You might be wondering: how is this different from other high-risk, high-yield private investments?

This is something many people get confused about, and I hope that by the time you finish reading this, you clearly understand the differences between venture capital and other forms of private investment.

To start with, venture capital focuses on investing in startups. Notice that I didn’t say "technology," even though many successful technology startups have been funded by venture capital.

What is a startup?

Nobody defines this better than Paul Graham.

“A startup is a company designed to grow fast. Being newly founded does not in itself make a company a startup. Nor is it necessary for a startup to work on technology, or take venture funding, or have some sort of "exit." The only essential thing is growth. Everything else we associate with startups follows from growth.”

This is the best definition of a startup I’ve seen so far. Basically, a startup is a small, early-stage company (in any industry, but typically involving new technology) that fundamentally changes how we live and do things and is designed to grow fast. Fast in this context refers to exponential growth, far beyond what most traditional businesses can achieve.

Think about it this way:

Imagine you stumbled upon an idea and invented something that could radically change the world. Every single person who came across your solution would need it so much that they would immediately pay you for it.

People buy your product, tell their friends and family, and every day your waitlist gets longer, your product keeps selling out, and you can barely keep up with the demand. You need to pay for additional raw materials, expand your factory, hire more customer support staff, improve the product, and increase advertising.

Technically, you could fund the growth of this company with the money that you make from customers, and grow steadily. However, if you choose to do that, it would mean that your growth is limited because while you’re still trying to figure things out and reinvest the money that you make from selling the product, a competitor with substantial capital could buy your product, reverse engineer it, build it and begin to sell. Because they have more capital, they can build a large factory, a worldwide distribution network, run advertisements, and run a smooth sales process.

So what do you do in this scenario where you have a great idea with proven value and a clear, growing target market?

Do you approach banks that require collateral and charge high interest rates? Even though your business is growing fast, you’re not really established yet, so they might deem you as high risk.

Do you approach a private equity fund? Even though you’re doing well, they might tell you that your volumes aren’t substantial enough and to come back when you’ve made significantly higher revenue.

In this scenario, the best option would be to raise capital from a venture capitalist. You take money from them in exchange for a share of ownership in your business. You could technically bootstrap the company and grow it on its own revenues, but you raise money from venture capitalists because it helps your company grow faster and meet the demand for your product. In exchange, the venture capitalist owns a part of your startup with the hope that they can sell their stake in the future, knowing that it is more likely that you die than succeed.

As Paul Graham puts it:

“If you want to understand startups, understand growth. Growth drives everything in this world. Growth is why startups usually work on technology — because ideas for fast-growing companies are so rare that the best way to find new ones is to discover those recently made viable by change, and technology is the best source of rapid change. Growth is why it's a rational choice economically for so many founders to try starting a startup: growth makes the successful companies so valuable that the expected value is high even though the risk is too. Growth is why VCs want to invest in startups: not just because the returns are high but also because generating returns from capital gains is easier to manage than generating returns from dividends.”

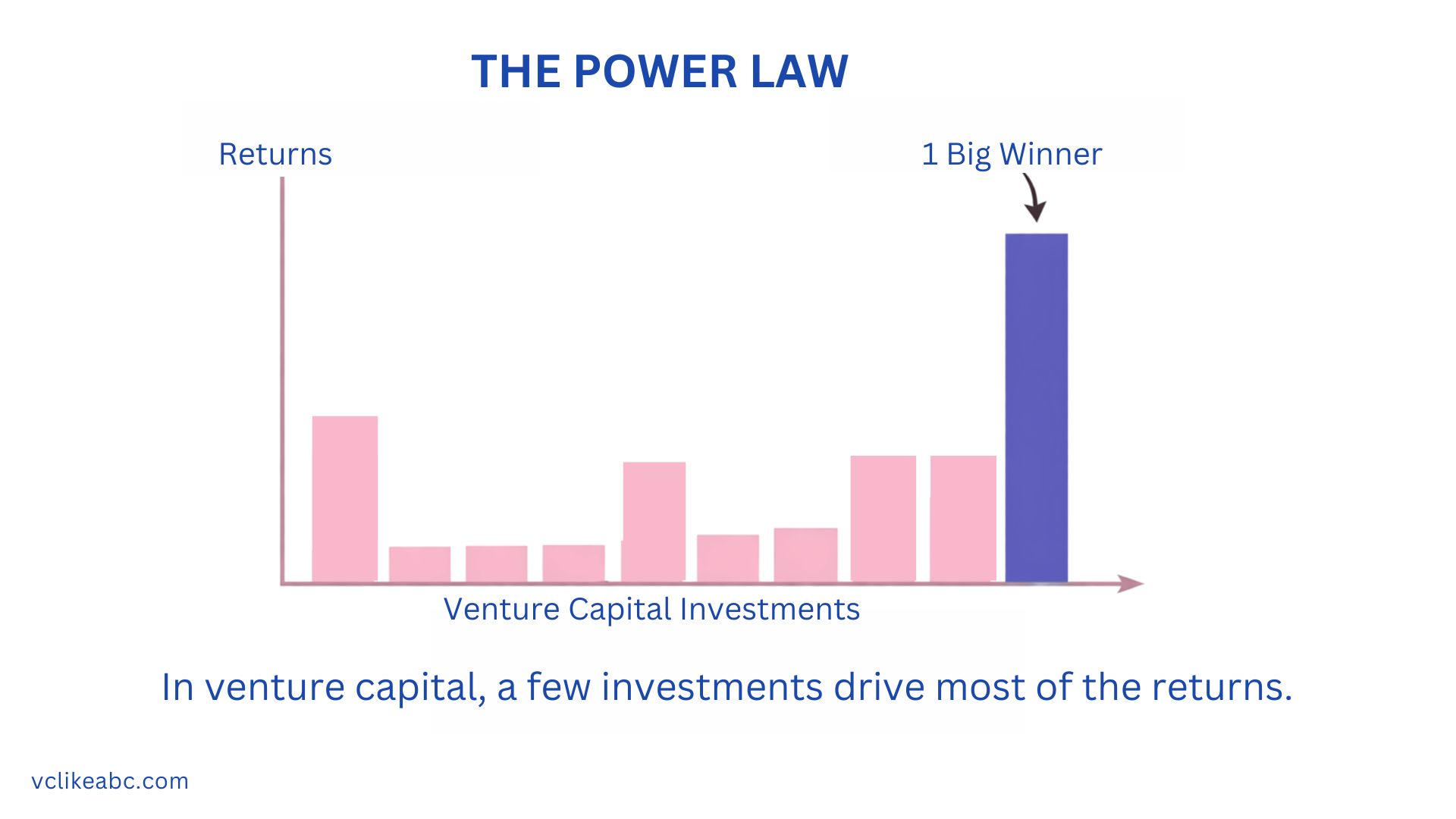

The Power Law

Venture Capital operates based on the power law.

The speed that powers startup growth comes with risk. There are many unproven assumptions and moving parts. Venture capitalists fund these risky, innovative companies, betting that if they grow instead of fail, they’ll make a lot of money. 9 times out of 10, they’re wrong. But they only need to be right once.

The power law holds that a tiny fraction of investments will produce massive returns; most will return little or nothing.

Private Equity vs. Venture Capital

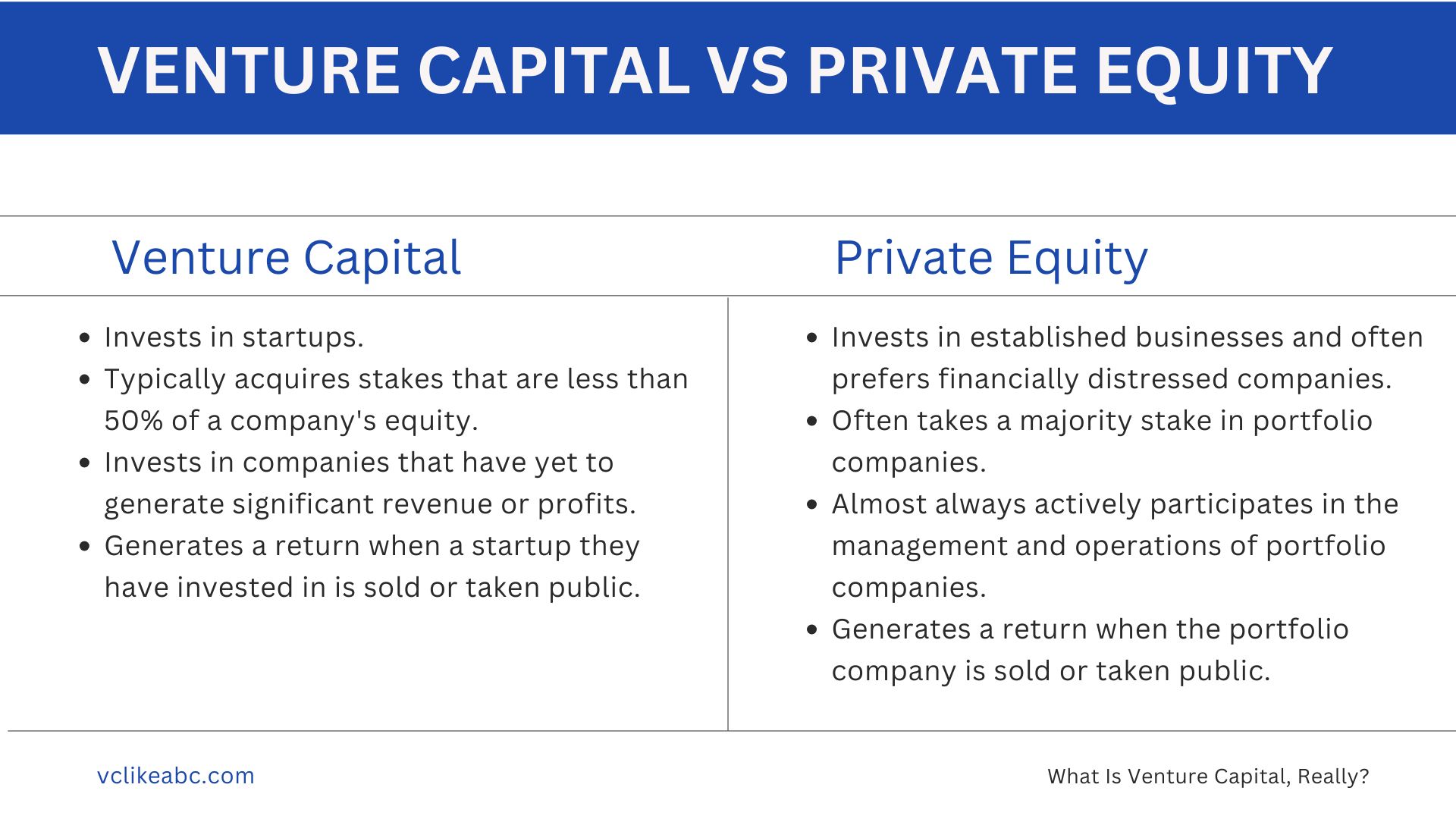

Venture capital is considered a form of private equity. The most apparent difference between them is that venture capital supports entrepreneurial ventures and startups, while private equity typically invests in established companies.

Putting it succinctly,

Venture Capital:

Invests in startups.

Typically acquires stakes of less than 50% in a company's equity.

Invests in companies that have yet to generate significant revenue or profits.

Generates a return when a startup they have invested in is sold or taken public.

Private Equity

Invests in established businesses and often prefers financially distressed companies.

Often takes a majority stake in portfolio companies.

Almost always actively participates in the management and operations of portfolio companies.

Generates a return when the portfolio company is sold or taken public.

Now that we’ve defined what venture capital is, let’s dig a little deeper into how exactly it all works.

Venture Capital is usually disbursed through a venture capital fund.

Traditionally, a venture capital fund is a private, pooled investment vehicle with a fixed term (usually 10 years) that invests in startups in exchange for equity. This is a privately held investment and cannot be accessed on the public market.

The fund’s assets are its portfolio, and the goal is to earn returns after a liquidity event. The fund is managed by a General Partner, who is responsible for raising capital for the fund, selecting investments, and managing its operations. General Partners are compensated via a 2% annual management fee and 20% carry (20% of the profits after a successful exit).

It is important to note that VCs only make money when there is an exit, such as an acquisition (being bought by a bigger company) or an IPO (being listed on the public market), because returns come from selling equity, not dividends. This structure aligns everyone's interests: the 2% fee covers the fund’s operating costs, while the 20% carry acts as a powerful incentive, rewarding the VC only when they successfully generate a profit for their Limited Partners.

The General Partner usually raises money from Limited Partners. These are high-net-worth individuals, financial institutions such as university endowment funds, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds, or even large corporations seeking exposure to the venture capital asset class. LPs choose to put their money here because, while risky, venture capital offers the potential for much higher profits than standard stocks or bonds, helping them diversify and grow their massive portfolios. Limited Partners are compensated with a return on their investment upon a successful exit.

Venture capital funds are typically structured under the assumption that fund managers will invest in new companies over a period of 2-3 years, deploy all (or nearly all) of the capital in a fund within 5 years, and return capital to investors within 10 years. This is a general guideline; in practice, many funds have different interesting structures.

In conclusion:

Venture capital is not about backing good businesses; it’s about backing the few businesses that can grow extraordinarily fast. Everything else about the model flows from that reality.

Understanding the "why" behind venture capital is the first step to mastering the industry. My goal with vclikeabc is to make these concepts stick, and I hope this first deep dive did exactly that.

If you enjoyed the read, please subscribe to receive future posts and share this with a friend who’s curious about VC.

What should I cover next? Share your thoughts and questions in the comments below. I promise to read every single one!